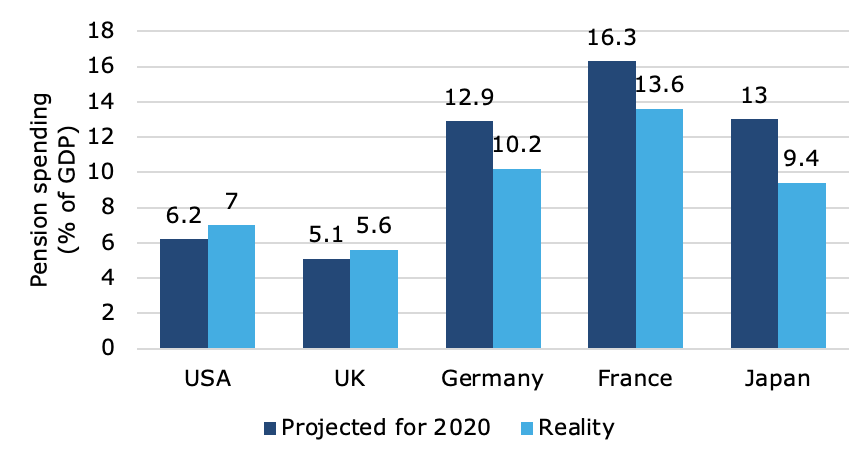

Obviously, we have been preoccupied with two major crises and their fallout over the last 13 years, so we may be forgiven if we lost track of another crisis that is looming in the background: the global retirement crisis. In 1995, the World Bank published a major analysis of the state of retirement systems around the world, which warned that around 2030, the social security systems in the United States and other industrialised countries would be running out of money. More prominently, a 2002 report by Richard Jackson, which was sponsored and then heavily promoted created an entire wave of investment reports on the topic. These reports focused on how the demographic changes and the retiring baby boomer generation are going to deplete social security and public pension systems and how we all have to save more in our private savings vehicles to overcome the shortfall in public pension benefits. 20 years after this important report it might be a good idea to check in on the retirement crisis and its current state. First, the bad news. The projections for the funding status of public pension benefits around the world have hardly changed over the last 20 years. I have gone through the long-term projections of the Social Security Trust Funds every year since 1980 and in each and every one of these projections the trusts are projected to run out of money sometime between 2030 and 2035. The same seems true for state pension benefit schemes in other countries like Switzerland. The year when they will run out of money has been remarkably constant and for most countries in Western Europe is sometime in the first half of the 2030s (though there are some exceptions). Then there is the mixed news. Going back to the 2002 report sponsored by Citi, we can compare the current state of government spending on pension benefits with the spending that was projected for 2020 twenty years ago. The chart below shows that for the United States and the UK the projections made two decades ago were pretty good and if anything too optimistic. Pension benefit spending over the last twenty years in these countries has increased more than anticipated. Government spending on pension benefits projected twenty years ago and reality Source: Jackson (2002), OECD But note that the three countries shown in the chart with the most severe demographic challenges and some of the most generous pension systems in the world (Germany, France, and Japan), have pension benefit spending that is much lower than anticipated. For these countries, the retirement crisis is less of a crisis today than it was twenty years ago. And this brings me to the good news (sort of). Countries with less sustainable pension systems have engaged in significant pension reform over the last twenty years, while countries like the UK and the United States that had less generous and thus more sustainable pension systems, to begin with, have not. This shows once more that demographics are not destiny because demographic projections that point to a major crisis in the distant future typically do not include the reaction of people to these crises. In the case of the retirement crisis, governments have kept costs under control by cutting benefits, increasing the retirement age, and increasing contributions. But before you start complaining about the massive tax increases and benefit cuts that are coming our way in the late 2020s, let’s look at a real-life example from the United States. Did you know that in the early 1980s the Social Security Trusts were projected to run out of money sometime between 1981 and 1983? The government of Jimmy Carter had less than five years to prevent US Social Security from failing. So, in 1977 Congress enacted a law that would increase payroll taxes for social security and disability starting in the 1980s and increase the maximum taxable income for social security. Between 1978 and 1983, the social security payroll tax increased from 10.1% to 10.8% and the maximum taxable income for social security purposes doubled from $17,700 to $35,700. But since that wasn’t enough to stabilise the trusts, President Reagan created a National Commission for Social Security Reform headed by Alan Greenspan. In 1983 Reagan signed the recommendations of this commission into law. The changes made were a continued increase in payroll taxes to 12.4% in 1990 and an increase in the retirement age to 67 by the year 2027. In total, an increase in payroll taxes by 2.3% over a decade and an increase in the retirement age over several decades managed to get the Social Security Trusts into a healthy surplus that lasted several decades. Today, the payroll taxes for social security still stand at 12.4% and the maximum taxable income has essentially increased with inflation since the Reagan reforms. Obviously, the demographic challenges waiting for us in the early 2030s are more extreme than the ones in the early 1980s, but this example shows one thing that is often overlooked by fearmongers. When it comes to retirement systems, small changes can have a large impact. All it takes to delay the retirement crisis by a couple of decades are a small increase in payroll taxes of 2% to 4% and an increase in retirement age by a couple of years. And my gut feeling is that if politicians can kick the can down the road with such small measures, they will do just that. So here is my prediction for the retirement crisis: Absolutely nothing will happen until at least 2028 and then governments in the United States and the UK as well as other countries will raise the retirement age to 70 years and increase payroll taxes by a couple of percentage points (just a little bit so as not to cost them too many votes). And we’re done. Then our children and grandchildren can take care of the rest in 2060 or 2070 when most of us are dead or long retired anyway. |

-

Archives

- April 2024

- March 2024

- February 2024

- January 2024

- December 2023

- November 2023

- October 2023

- September 2023

- August 2023

- July 2023

- June 2023

- May 2023

- April 2023

- March 2023

- February 2023

- January 2023

- December 2022

- November 2022

- October 2022

- September 2022

- August 2022

- July 2022

- June 2022

- May 2022

- April 2022

- March 2022

- February 2022

- January 2022

- December 2021

- November 2021

- October 2021

- September 2021

- August 2021

- July 2021

- June 2021

- May 2021

- April 2021

- March 2021

- February 2021

- January 2021

- December 2020

- November 2020

- October 2020

- September 2020

- August 2020

- July 2020

- June 2020

- May 2020

- April 2020

- March 2020

- February 2020

- January 2020

- December 2019

- November 2019

- October 2019

- September 2019

- August 2019

- July 2019

- June 2019

- May 2019

- April 2019

- March 2019

- February 2019

- January 2019

- December 2018

- November 2018

- October 2018

- September 2018

- August 2018

- July 2018

- June 2018

- May 2018

- April 2018

- March 2018

- February 2018

- January 2018

- December 2017

- November 2017

- October 2017

- September 2017

- August 2017

- July 2017

- June 2017

- May 2017

- April 2017

- March 2017

- February 2017

- January 2017

- December 2016

- November 2016

- October 2016

- September 2016

- August 2016

- July 2016

- June 2016

- May 2016

- April 2016

- March 2016

- February 2016

- January 2016

- December 2015

- November 2015

- October 2015

- September 2015

- August 2015

- July 2015

- June 2015

- May 2015

- April 2015

- March 2015

- February 2015

- January 2015

- December 2014

- November 2014

- October 2014

- September 2014

- August 2014

- July 2014

- June 2014

- May 2014

- April 2014

- March 2014

- February 2014

- January 2014

- December 2013

- November 2013

- September 2013

- August 2013

- July 2013

- June 2013

- May 2013

- April 2013

- March 2013

- February 2013

- January 2013

- December 2012

- November 2012

- October 2012

- September 2012

- August 2012

- July 2012

- June 2012

- May 2012

- April 2012

- March 2012

- February 2012

- January 2012

- December 2011

- November 2011

- October 2011

- September 2011

- August 2011

- July 2011

- June 2011

- May 2011

- April 2011

- March 2011

- February 2011

- January 2011

- December 2010

- November 2010

- October 2010

- September 2010

- August 2010

- July 2010

- June 2010

- May 2010

- April 2010

- March 2010

- February 2010

- January 2010

- December 2009

- November 2009

- October 2009

- September 2009

- July 2009

- May 2009

- April 2009

- January 2009

-

Meta

It’s all very well increasing the minimum State Pension age to 70 to save money on payments to Pensioners, but do the calculations include the cost of benefits that will have to be paid to youngsters because the pensioners are still doing the jobs that should be done by “school leavers”? Or, as I suspect, is this cost ignored?